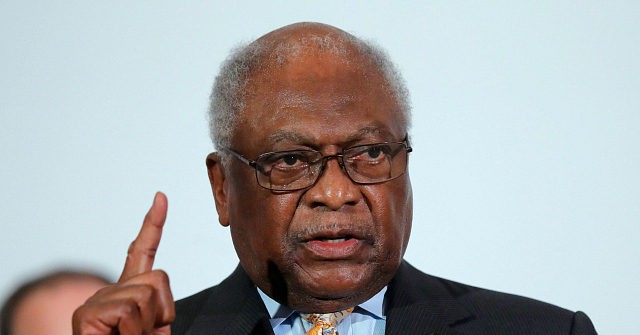

Rep. James Clyburn (D-SC) trotted out a now-familiar defense of President Joe Biden on Sunday morning against the impeachment inquiry against him: he was just doing what any dad would do when he helped his son, Hunter Biden, make money from access to power.

Alternatively, this defense holds that Republicans are mean because Biden was just trying to help a son struggling with addiction.

I don't know what the truth is in the Biden family, nor does anyone else. I do know there was a glaring conflict of interest, which even the Obama administration flagged, and there is good evidence of corruption implicating Biden as well as Hunter and the family.

What I mean is that I don't know about the father-son relationship. I tried writing about it last week, and stopped, because I don't know.

I do suspect that there is a possibility Joe Biden used his son to go on foreign errands for cash -- and that he might even have enabled, or ignored, Hunter Biden's addictions, in doing so. Maybe he even thought the addictions were helpful: it meant Hunter Biden could be told to do things other people ordinarily wouldn't, because he was desperate for cash and knew how to manipulate people to get it.

I think that could be true; I also think Biden could just have been worried about his son when he staged a reported intervention in 2019. Maybe he was just worried about his 2020 run. Who knows.

What I do know is that this was not just as simple as a father's love for his son. This was also about Joe Biden's own greed. One part of the story does not negate the other, but both stories must be told.

This week’s portion launches the great story of Abraham, who is told to leave everything of his life behind — except his immediate family — and to leave for “the Land that I shall show you.”

There’s something interesting in the fact that Abraham is told to leave his father’s house, as if breaking away from his father’s life — but his father, in fact, began the journey, moving from Ur to Haran (in last week’s portion). His father set a positive example — why should Abraham leave him?

Some obvious answers suggest themselves — adulthood, needing to make one’s own choices, his father not going far enough, etc.

But I think there is another answer. Abraham (known for the moment as Abram) needs to establish his own household. This is not just about making one’s own choice, but really about choosing one’s own starting point. It’s starting over.

Sometimes we start over in fundamental ways even if much that surrounds us remains the same. Sometimes the journey we have to ...

The story of Noah is familiar; the details, less so.

Noah is often seen as an ambivalent figure. He was righteous -- but only for his generation. What was his deficiency?

One answer suggests itself: knowing that the world was about to be flooded, he built an Ark for the animals and for his own family -- but did not try to save anyone else or to convince them to repent and change their ways (the prophet Jonah, later, would share that reluctance).

Abraham, later, would set himself apart by arguing with God -- with the Lord Himself! -- against the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, saying that they should be saved if there were enough righteous people to be found (there were not).

Still, Noah was good enough -- and sometimes, that really is sufficient to save the world. We don't need heroes every time -- just ordinary decency.

Hi all -- as I noted last month, I'm going to be closing down my Locals page, at least for tips and subscriptions -- I may keep the page up and the posts as well, but I'm no longer going to be accepting any kind of payment.

Look for cancelation in the very near future. Thank you for your support!